The hardships suffered by captured Shields fishermen

She highlighted the plight of local fishermen who were feared lost after their boat, the St George had been missing for three months before word arrived that its nine-strong crew (made up of North and South Shields men) was being held captive in a German POW camp, near Berlin.

Today Dorothy tells us more about the mens’ capture and the appalling conditions they found themselves being held in.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis information came via Alec Barclay, who was liberated from Ruhleben POW camp in 1915 where he had met the skipper of the St George, Captain William Hastie.

“Capt. Hastie had assured him that when captured, their trawler was definitely in British waters,” Dorothy explains.

“The commander of the German submarine had alleged that the St George had tried to ram him, and according to Hastie made that the excuse for his abominable conduct towards them.

“Their trawler was sunk and Capt Hastie and crew taken aboard the U-Boat where, for 48 hours, they were guarded by Germans with drawn revolvers who treated them very badly.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat U-Boat, U41, commanded by Claus Hansen, was responsible for the sinking of 30 ships in 1915 alone before being sunk off the Scilly Isles by HMS Baralong.

The loss of the St George was witnessed by the trawler St Louis, whose crew described hearing a very loud explosion as if the vessel had been torpedoed.

“The crew were first interned at Sennelager, a camp with a rather bad reputation, but were subsequently sent to Ruhleben.

“Hastie had told Barclay that there was another trawler near the St George but it cut its gear and cleared off before being attacked.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Barclay said the prisoners at Ruhleben were in quite good health, with no thanks to their German hosts, but rather to the lifesaving supplies of food and comforts sent to them from the British people.”

Unaware of the crew’s fate, it was reported that, in three cases, insurance money was paid out to the presumed widows.

The men, meanwhile, were having to cope with life as captives in the enemy’s homeland, initially at the notorious Sennelager Camp, and then at Ruhleben.

At Sennelager, the prisoners slept during the heat of the day and kept moving during the night to keep warm.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Food was in very short supply,” said Dorothy, “with a main meal at lunchtime of thin cabbage soup. Then they were moved to tents which held 600 men, but they still slept on the ground. There were no means to wash their clothes. All prisoners were glad to leave this place.”

However, Ruhleben, a former racetrack, was little better, and only made slightly more bearable by the intervention of the American Embassy.

“Letters from the camp were subjected to severe censorship and reports suggested that pressure was placed upon prisoners to describe conditions better than they were in reality.

“The US ambassador described the barracks as overcrowded and it seemed intolerable that six people should be herded together in a horse’s stall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Conditions in the haylofts above the stables were even worse. Sixty four men lived in that confined space with light so faint that prisoners eyes, wrote the Ambassador, ‘will be seriously injured, if the sight is not permanently lost’,

“Straw sack mattresses were often stuffed with wet and mouldy straw. Many of the horse stalls had manure still clinging to the whitewashed walls and cement floors.

“Food was meagre and of bad quality, and according to the ambassador, prisoners were at risk of starvation.”

Ablutions for 250 men were done via 20 basins, filled at one cold water tap.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEventually, following pressure from the American Embassy, the Germans built four new barracks.

Interned British engineers put in drainage, latrines and washing facilities while the American YMCA donated and built a hut.

The captives created a garden which provided the camp kitchen with fresh fruit and vegetables. They also produced a camp magazine. Permission was also given to organise games.

Dorothy goes on to reveal that, with funds provided by the American Embassy, the prisoners built a boiler house to provide hot water and at last camp life improved dramatically.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At the end of November, 1918, the Shields men returned home from Ruhleben camp after three years of captivity.

“One of them, Robert Craig, was met at the railway station by ecstatic members of his family and a large gathering of enthusiastic townsfolk.

“He said 15 other men from North Shields were among a large batch of released prisoners to be landed at Hull.

“It must have felt so good to be back on Tyneside,” added Dorothy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

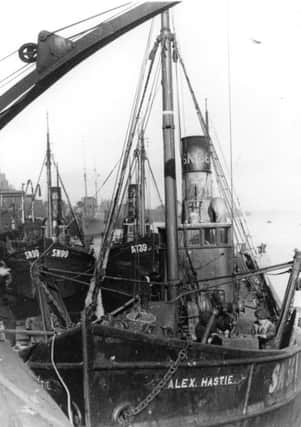

Hide AdThe crew of the St. George were: 1) Skipper William Hastie, of King Street, North Shields; 2) RH Craig, Mate, of North King Street, North Shields; 3) JR Sutherland, Engineer, of Yeoman Street, North Shields; 4) JR Turnbull, Second Engineer, of Yudyard Street, North Shields; 5) Richard Wilson, Fireman, of Back Street, Preston, North Shields; 6) Joseph Laws, Deck Hand, of Bowman Street, South Shields; 7) HG Roberts, Deck Boy, of Alfred Street, South Shields; 8) Charles Brown, Third Hand, of Reay Street, South Shields and 9) Charles Ormsby, Cook, of Stewart Buildings, North Shields.

l Hearing of Dorothy’s account, Mr Henry Howard, Vice Chairman of the North Shields Fishermen’s Heritage Project (NSFHP) got in touch to say: “This is a subject close to our hearts and ties in with one of the objectives of our group – remembering those who have lost their lives from the river Tyne.

“I know readers will be familiar with the tremendous community effort that raised £75,000 for the Fiddlers Green Memorial and the chord it struck with everyone in the local area.

“We are continuing to fundraise for a memorial book where we can record the names of the many men who lost their lives from the river.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We are looking to raise £7,000 for the book, the calligraphy and a secure glass. The book will be held The Old Low Light Heritage Centre.

“Donations should be sent to the NSFHP at The Old Low Light Heritage Centre, Clifford’s Fort, North Shields Fish Quay. NE 30 1JA.”