Food parcels helped provide cheer for POWs

On the first occasion, in 1918, he was so badly scalded that he wasn’t expected to live. Twenty two years later, he was taken prisoner and held captive in a prison camp called Milag, in Germany.

John, a third engineer, was incarcerated there for more than three years until 1943 when he was repatriated due to the fact that he was 63 years old and in ill health.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHaving been handed a pass, allowing safe passage through Germany, he travelled by train to Sweden, where he received a package of sweets, fruit and razor blades, before joining the Empress of Russia ship in Gothenburg which brought him back to England.

Once home, at Commercial Road, South Shields, John was interviewed by a Shields Gazette reporter who recorded his experiences.

This is what he wrote. In reply to a question as to how he was treated when in captivity, Mr Aikenhead said: “We were not badly treated by our captors.

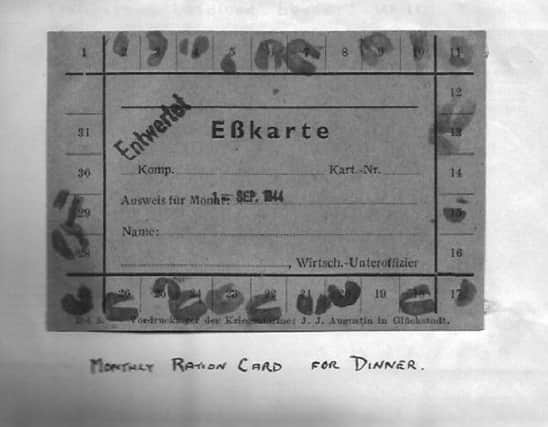

“The rations at first were meagre, but they improved later.

“Without the parcels we received from the Red Cross and Merchant Navy Comforts Fund, however, our lot would have been much worse.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Our dinner generally consisted of stew and potatoes, and for breakfast and tea we usually had dry rations.”

John said all things considered they had little to complain of though there was always the barbed wire to remind them if any reminder was necessary, that they were not their own masters.

“The guards carried out their duties humanely, though occasionally prisoners became refractory and were punished by solitary confinement or a reduction in rations.

The news of the outside world, apart from letters which reached us fairly regularly, was for the most part restricted to what appeared in a camp newspaper, published in Berlin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As regards the war, the news was not reliable, but reading between the lines, the prisoners were able to form their own construction.”

He added that sometimes their guards gave them information regarding the fortunes of those involved in the conflict.

When asked about camp routine, John told the reporter how the older men, himself included, were not called upon to do any manual work, but some of the younger men when requested to help local farmers, and were glad of the opportunity of getting away from camp routine.

It was surprising how quickly the days passed, he remarked, thanks to cards and wooden horse races.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe camp also boasted four orchestras and there were times when merchant navy men entertained their fellow prisoners with plays.

Mat and model making were favourite ways of passing the time.

“There was an arts and crafts exhibition which “showed evidence of surprising skill”.

“We had dances,” he said, “but there were no lady partners!”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen Alan’s grandad returned home, he retired, but helped out at Stephenson’s Haulage in Commercial Road. He also spent time as a football coach.

Born in 1879, John died in 1954 at the age of 75.

Paying tribute to his grandad, Alan said: “He was an amazing man; he never called the Germans and was a most gentle man.

“He was such a patient man who never lost his temper,” added Alan, himself a former Merchant Navy engineer who is 75 years old.