What life was like for this South Shields prisoner of war

“The Red Cross sent packages of games and entertainment to the prisoners to alleviate their boredom,” explains Pamela. “Other entertainment would be journals to write, plays to perform, football matches and vegetable gardens where they grew anything from potatoes to tomatoes and flower beds. Some camps had a regimental bands to provide musical entertainment.”

At the end of the war, the British prisoners were released without any food, resulting in many of them dying from exhaustion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose that survived were sent back through the lines in lorries to reception centres where they were refitted with boots and clothing. After a medical examination they were dispatched to sea ports in trains.

Each man was given a message from King George V, written in his own hand, reading: “The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries and hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage. During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant officers and men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.

“We are thankful that this longed-for day has arrived, and that back in the old country you will be able once more to enjoy the happiness of a home and to see good days among those who anxiously look for your return. George R.I.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

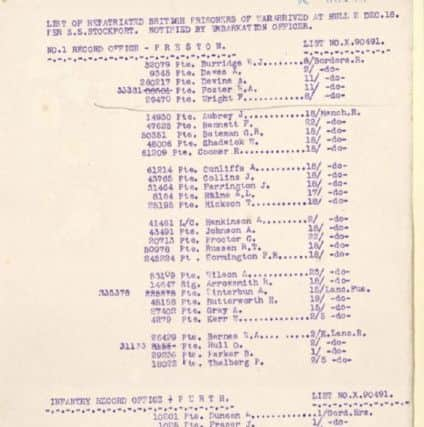

Hide Ad“Hull was affectionately known as the ‘Home to Blighty’ and received more than 80,000 repatriated prisoners of war through its ports.

“They received a hearty welcome when they landed at the riverside quay, greeted by huge crowds and a chorus of sirens. The bands played “See the Conquering Hero Comes,” “Home, Sweet Home” and “Auld Lang Syne”.

“Trains ran from the docks to Ripon where motorised transport took them from the station to the Ripon Camp Dispersal Centre.”

Here Arthur would have received: A railway ticket to South Shields; a certificate enabling him to receive medical attention if necessary during his final leave; an Out-of-work Donation Policy, which insured him against unavoidable unemployment of up to 26 weeks in the following 12 months; an advance of pay; a fortnight’s ration book, a voucher (Army form Z50) for the return of his greatcoat to a railway station during his leave and either a clothing allowance of 52 shillings and sixpence or be provided with a suit of plain clothes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Arthur’s final ‘leave’ began the day after he was dispersed and he went home, still in uniform and with his steel helmet and greatcoat. Legally he could not wear his uniform after 28 days from dispersal.

“During leave he had to go to a railway station to hand in his greatcoat for which he was paid £1.

Pamela says the family legend tells how: “Arthur spent the entire war in salt mines in Germany, and that he was brought home wrapped in a bale of cotton”.

“From this, I can only assume that Arthur had injuries heavily padded to protect them on his voyage home. The seriously sick cases were put into hospital at Hull, and the slightly sick cases were taken to the King George Hospital; the sound men going to Ripon. I have come across so many family legends, some I have proven as true and some not, however, I’ve yet to find the evidence that Arthur was injured.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArthur was awarded the 1914 Star, British War Medal and the British Victory Medal.

“Following repatriation, he married a local lass named Annie Scott in June 1919 and they had two children, Nancy, born in 1922, and Edith, in 1925.

“In July 1937, at the age of 48, Arthur died whilst at work in Readheads Shipyard. He was buried in a public grave in Harton Cemetery.”