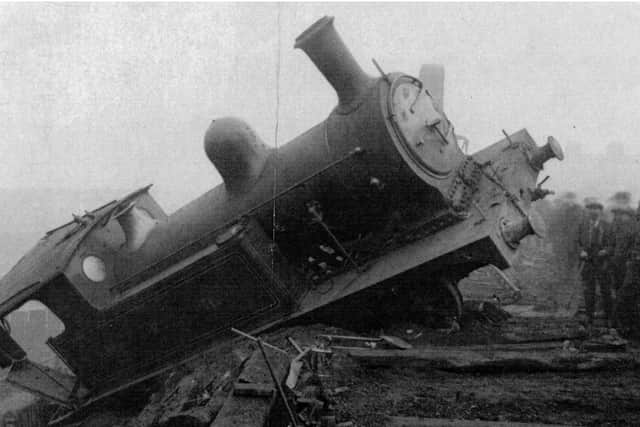

The Jarrow rail disaster - a century on from the devastating three-train collision that killed 18 and injured 81

and live on Freeview channel 276

The story of the Jarrow rail disaster led to an inquiry after a collision that killed 18 people, the youngest being just 14, and injured 81.

The crash

December 17, 1915 was a dark, foggy morning south of the River Tyne.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe railway line there had a gradient as sharp as 1 in 49 in places, very steep for regular rail. A goods train was being “banked” by another locomotive, ie. shoved from behind to help it uphill.

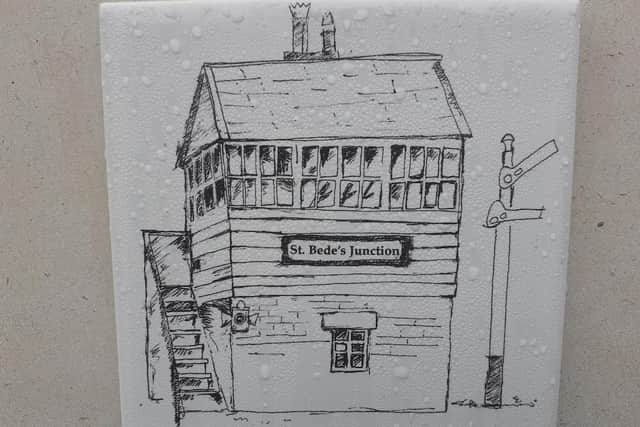

The “banker” carrying out the shoving, tank locomotive 2182, was not coupled (linked) and was eventually rolled back from the goods train to a standstill along the line. It then waited at its usual place and whistled to signal its completed task. But this went unnoticed by the signalman.

The banker’s driver, William Hunter, became concerned and now applied “Rule 55”. This meant essentially that his whistle had not been acknowledged and that a crew member should go to the nearest signal box on foot and tell the signalman in person.

Mr Hunter sent his fireman (stoker), Robert Jewett, to inform signalman William Hodgson. Before Mr Jewett got there he could hear the 7.05am west-bound South Shields to Newcastle service approaching. This was a passenger train with seven carriages. The signalman had given it clearance.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had also cleared the east-bound 6.58am Hebburn to South Shields service, another eight-carriage goods train, although it was empty.

Mr Jewett reached the box and Mr Hodgson immediately acted and changed the signals to show danger. He was too late.

Back in the banker, Mr Hunter could see the train approaching from behind and tried as quickly as he could to move his engine forward.

The passenger train was travelling at 30mph and at 7.20am crashed into the back of Mr Hunter’s locomotive, which had only just begun to move forward again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Hunter was knocked unconscious. When he came round he was in a field at the bottom of the embankment. Both engines were derailed.

The ensuing wreckage back on the track was then struck by the 6.58am, travelling in the opposite direction at 10mph. All three engines were now at the bottom of the 20ft embankment; two on one side, one on the other.

The greatest part of the disaster was the fate of the two leading carriages of the passenger train, which “telescoped” – they ended up one on top of the other.

A few minutes after the collision, fire broke out accelerated by gas pipes breaking (carriages were lit by gas lamps). It destroyed the first carriage and much of the second.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt could have been worse. William Dunlop and William Rowe, driver and guard respectively of another train which had been waiting to depart, rushed to uncouple the other carriages and push them away before the fire spread.

The enquiry – and the blame

An enquiry was conducted by Lieutenant-Colonel Pelham George von Donop; a very interesting character. He was a former England international footballer and godfather to the author PG Wodehouse, who was named after him.

After leaving the Army, von Donop became an inspecting officer of railways for the Board of Trade’s Railway Inspectorate. He did not hold back with his criticism of the North Eastern Railway Company. Enquiries moved more quickly in those days and the report was published on February 3, 1916.

Von Donop concluded that one of the contributing factors was that, as bankers were not always used, a signalman might overlook its presence. This was compounded by signalman Hodgson neither seeing nor hearing the engine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBell codes used between signal boxes were changed as a result, to signify whether a banker engine was present or not.

The individual to receive most of the blame was William Hunter – driver of the banker with 23 years experience. The thick fog should have meant that he activated “Rule 55” immediately. But 17 minutes elapsed before he sent Mr Jewett to the signal box.

William Hodgson, a signalman for 40 years, did not escape culpability either. A banker was used on half of the trains on this particular line, so he must have known that it could well have been used to shunt the earlier goods train, although in this case he did not know whether a banker had been used or not.

Both men would have to live with the events of that day.

Lt-Col von Donop also recommended that gas lighting on trains should be replaced by electric, but it was some years before this was carried out. He concluded too that the fire extinguishers had been almost useless.

Aftermath and commemoration

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll crewmen survived, but according to von Donop’s report: “Eighteen passengers in this train, most of whom were travelling in the leading vehicle, were killed, and it is believed that all those killed in that vehicle were killed instantaneously by the collision.

"Their bodies were however subsequently completely consumed by fire.”

The youngest victim was 14 year-old Alban Sweeney. A further 81 were injured.

Today there is nothing to mark the crash’s exact location. However, on December 17, 2015, exactly 100 years later, a memorial stone bearing the names of 17 of the dead was unveiled in Harton Cemetery in South Shields.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt isn’t some sort of macabre competition, but more recent rail disasters at Potters Bar and Selby, which received blanket media attention, were thankfully not as deadly. So why does the Jarrow crash have such a relatively low profile?

As 1915 was a year of global carnage, including at Ypres and Gallipoli, as well as the Quintinshill rail disaster in Scotland in May which claimed 226 lives, it’s easy to see why Jarrow is an obscure event to the wider world. But that doesn’t lessen the tragedy, which still looms large.