The story of the Seven Men of Jarrow - striking miners who were deported to Australia over a crime they probably didn't commit

and live on Freeview channel 276

It wasn’t even particularly well known in the North East until Jarrow MP Ellen Wilkinson wrote about it in her 1939 book The Town That Was Murdered.

The Tolpuddle Martyrs are world famous. The story of the seven Devon farm workers, deported to an Australian penal colony in 1834 for objecting to a 40% wage cut, is perhaps the most famous in the history of trade unions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the story of the Seven Men of Jarrow took place in 1832 – two years before Tolpuddle.

Saturday, July 3 will see commemorations for the fourth year running of the miscarriage of justice that still draws resentment today.

Here is the story of the seven, with thanks to David Douglass, local historian and secretary of the Follonsby Wardley Miners Lodge Banner Community Heritage Group who plans to publish a book on the Pitmen’s Union later this year.

Background

In 1824 the first official miners union, the United Colliers of Northumberland and Durham Association, was founded by Tommy Hepburn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

He was a natural leader who had started work in the pit at Fatfield, now part of Washington, aged just 10. This was not remarkable at the time. Others were as young as six.

The union became known as Hepburn’s union. Even the most committed union bashers of the 21st century would concede that miners had some very legitimate grievances back then, amid some horrendous working practices. Nevertheless, its mere existence infuriated mine owners.

The first aim addressed by the union, leading to an 1830 coalfield strike, was a reduction in hours for workers carrying out shifts of up to 18 hours a day. The strike, led by Hepburn, was victorious and the maximum shift was reduced to a comparatively luxurious 12 hours a day.

The coalfield owners of Durham and Northumberland, usually super-rich aristocrats such as the notorious Londonderry family, were not amused.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

The third Marquess of Londonderry would fly into a rage at the suggestion that child labour should be abolished. Mine owners did not take kindly to any sort of demand for workers’ rights. This is what mining families were up against.

Violence escalates

After 1830 according to David Douglass: “the owners and the law unleashed harsh repression on the miners and their families, evicting them from their houses, dispersing pickets and demonstrations often with armed police, cavalry and at times gun fire was exchanged.”

There was considerable violence in 1832, which resulted in 10 miners from Jarrow being arrested and charged with robbery with violence. All 10 of the men were prominent members of the Hepburn union.

It should be said that not all of the 10 men were without sin. Two of them had burgled a wealthy couples’ house where they demanded cash and meat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe wife was first to be attacked, followed by her husband when he came downstairs to see what all the commotion was about and the burglars made off with a small amount of money and a pistol.

Despite only two people being involved with this rather nasty crime, all 10 of the union men were rounded up and charged under joint enterprise.

Three of the men managed to escape. The other seven were deported to Australia and put to work in mines there; presumably in even worse conditions.

They were “let off” with deportation as they were originally sentenced to death for a crime they may or may not have known about.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe seven men were Thomas Armstrong, John Barker, Isaac Ecclestone, David Johnson, John Smith, Batholomew Stephenson and John Stewart.

The judge did not regard their union activities in a positive light. Effectively it was striking and union activity that had landed them in the dock.

None of the seven would ever return to England.

William Jobling ‘the eighth martyr’

Violence escalated after the verdict. Strike breakers were attacked, a miner was shot dead, families evicted, strike meetings were attacked by armed police.

In once incident a miner’s wife was deported to hard labour while others were beaten down by metal bars used to break into miners’ homes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFollowing the killing of a magistrate, 71 year-old Nicholas Fairles, two men were arrested. One of them was Ralph Armstrong who was the brother of the deported Thomas Armstrong.

Ralph was identified by Fairles, who died 19 days after the attack. Armstrong’s companion, William Jobling, was arrested and tried, again under joint enterprise.

It was Armstrong who had struck the fatal blow to Fairles with a stick, but Jobling who was charged with murder.

Armstrong, clearly the more culpable of the pair, went on the run and was never seen again. Jobling was eventually sentenced at Durham to be hanged on August 3, 1832. The jury took 15 minutes to reach their verdict.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

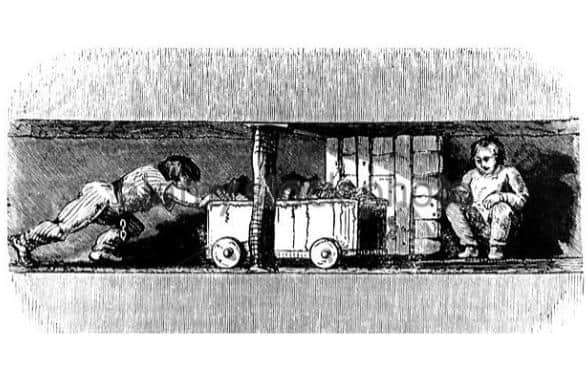

Hide AdJobling was the second-last man in Britain to be gibbeted (James Cook of Leicester was last). Gibbeting involved hanging the guilty (or not) party before displaying the rotting corpse in a cage as a warning to potential wrongdoers.

Jobling’s body was covered with pitch, caged and paraded through pit villages, then placed opposite his house where his family were still living.

His body was later surreptitiously moved by friends and buried near the spot in Jarrow now marked by a granite rock. He was at least as much of a martyr as the Seven Men of Jarrow.

William Jobling had also been a striking miner.